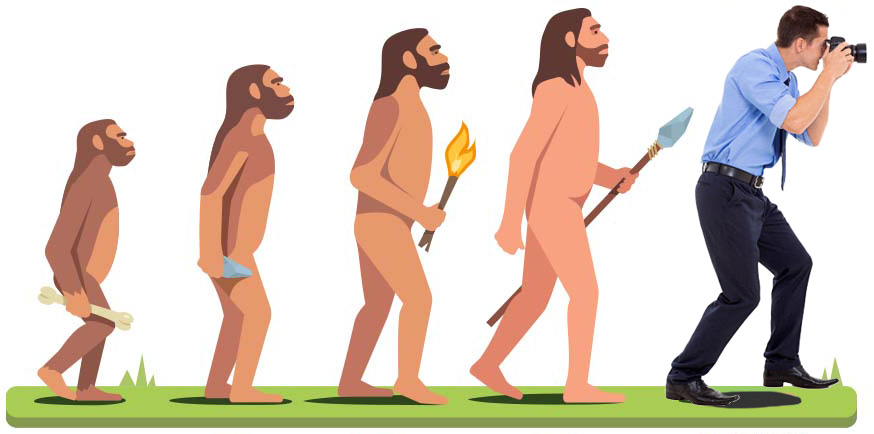

Reflecting on the "Four Stages of Photographer Evolution"

...in which I respond to a fellow Substack photographer's description of a prototypical photographer's journey, vis-à-vis their gear

I read a great article last week by Cedric at “I May Be Wrong” and wanted to use it as a jumping-off point to add my own commentary. I’m largely in agreement with his thesis and framing, even down to…